The majority of the garment industry’s workers in Bangladesh are women – up to 80 per cent by some estimates. Many of Bangladesh’s workers are migrants from rural area – without networks of family or friends and women must often choose between unemployment or working while leaving their children behind to fend for themselves.

One social entrepreneur, however, has steadily made progress partnering with communities and garment factories to improve the lives of women workers and their children. Ashoka Fellow Suraiya Haque founded Phulki in 1991, and today the organisation operates nearly 90 community-based, and 25 factory-based daycares in Dhaka.

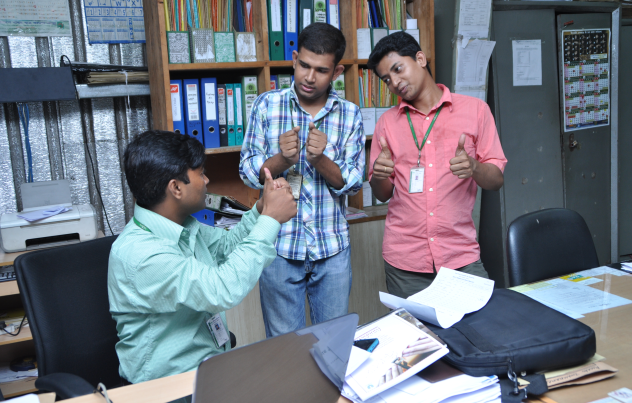

Caretakers at the daycares are trained in early childhood development, nutrition, and hygiene. And each month, Phulki meets with mothers – and occasionally fathers – for nutrition education, and offers trainings on labour, sexual, and reproductive rights.

Phulki means “spark” in Bangla. The name reflects the organisation’s broader mission to kindle the socio- economic development of female workers, and to serve as “a flicker of light to the lives of disadvantaged communities.” Its innovative model ultimately uses

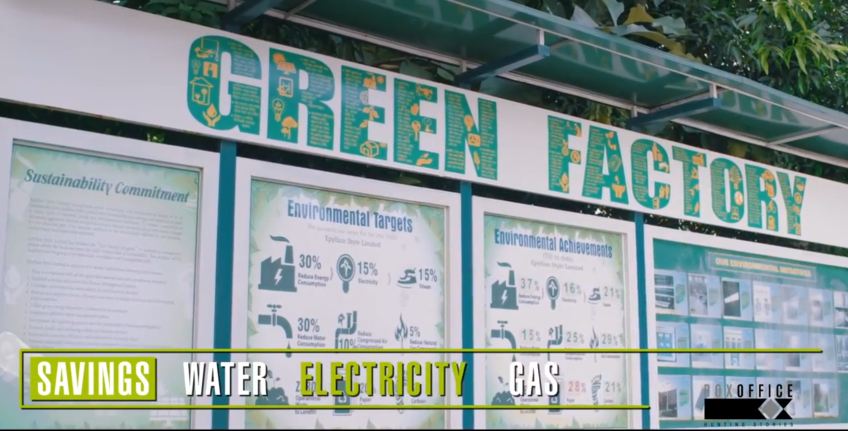

Childcare services as a launching point to deliver life- saving, health-related information to all workers. With the consent of factory management, Phulki also conducts a health awareness initiative at factories. This year, 90,000 men and women workers completed the program.